Calderdale history timeline 1810 - 1850AD

Industrial Revolution

From

the late eighteenth century, technological innovation in the textile

industry advanced. It led to the proliferation of more water-powered

cotton and worsted spinning mills and woollen scribbling (carding)

mills. Also, their dams, goits and sluices in the tributary

valleys of the Calder. The need for more effective means of transportation

resulted in the construction of canals. Also, a network of turnpike roads

along the valley bottom. This progressively replaced the old hillside

packhorse ways. See the Acts

of Parliament, 1757, 1769, 1810 and the plan of the river Calder

above.

From

the late eighteenth century, technological innovation in the textile

industry advanced. It led to the proliferation of more water-powered

cotton and worsted spinning mills and woollen scribbling (carding)

mills. Also, their dams, goits and sluices in the tributary

valleys of the Calder. The need for more effective means of transportation

resulted in the construction of canals. Also, a network of turnpike roads

along the valley bottom. This progressively replaced the old hillside

packhorse ways. See the Acts

of Parliament, 1757, 1769, 1810 and the plan of the river Calder

above.

During

this first phase of industrialisation, religious nonconformity underwent

a dramatic renewal, reinforcing the industrial work ethic. By

1800 both chapel and mill were beginning to make their mark on an

increasingly urbanised landscape (see Square chapel opposite).

During

this first phase of industrialisation, religious nonconformity underwent

a dramatic renewal, reinforcing the industrial work ethic. By

1800 both chapel and mill were beginning to make their mark on an

increasingly urbanised landscape (see Square chapel opposite).

Although there is clear surviving evidence of its pre-industrial origins. The spatial structure of present-day Halifax is very much a product of the complex process of industrialisation. this took place between the mid 18th and late 19th centuries.

In

1750, Halifax was a small but busy market town, with a population of

approximately 6,000 inhabitants. It was served by a network of ancient packhorse

causeways. The common fields and waste had long since become a series

of dry-stone wall enclosures. The growing numbers of inns and

streets must have given the town something of an urban atmosphere. Most

of the population was centred on the small urban nucleus however. Public buildings, such as the church and manorial moot hall, were

still medieval in origin. Almshouses, an orphan hospital, charity

schools, a mulcture hall, workhouse and cloth halls made their

mark on landscape.

In

1750, Halifax was a small but busy market town, with a population of

approximately 6,000 inhabitants. It was served by a network of ancient packhorse

causeways. The common fields and waste had long since become a series

of dry-stone wall enclosures. The growing numbers of inns and

streets must have given the town something of an urban atmosphere. Most

of the population was centred on the small urban nucleus however. Public buildings, such as the church and manorial moot hall, were

still medieval in origin. Almshouses, an orphan hospital, charity

schools, a mulcture hall, workhouse and cloth halls made their

mark on landscape.

By

1800 the town of Halifax was expanding and the population had increased

to almost 9,000. Elegant Georgian mansions were built, like Clare Hall (1764),

Hope Hall (1765) and Somerset House (1766 - see opposite). This was the emergence of a narrow band of upper status mercantile households

on the outskirts of the business district. The

pre-eminence of Halifax as a cloth marketing centre received its most

striking expression in the Piece Hall (1779). This opened as certain

aspects of the domestic era were already drawing to a close.

By

1800 the town of Halifax was expanding and the population had increased

to almost 9,000. Elegant Georgian mansions were built, like Clare Hall (1764),

Hope Hall (1765) and Somerset House (1766 - see opposite). This was the emergence of a narrow band of upper status mercantile households

on the outskirts of the business district. The

pre-eminence of Halifax as a cloth marketing centre received its most

striking expression in the Piece Hall (1779). This opened as certain

aspects of the domestic era were already drawing to a close.

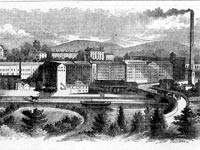

During

the first half of the 19th century a second wave of industrialisation

swept through the upper Calder valley. This dramatically transformed the

landscape and the whole social fabric of the district. With the introduction

of steam power, the textile industry moved to the more accessible

valley bottom settlements. These were Todmorden,

Hebden Bridge, Mytholmroyd,

Sowerby Bridge, Halifax,

Elland and Brighouse.

This left more ancient communities stranded on the hillsides and taking

with it an expanding population of millworkers. In Halifax, steam

powered textile factories spread rapidly and by 1850 there

were 24 mills in the town. The largest of which were at Boothtown

(James Akroyd & Son) and Dean Clough (John Crossley & Sons).

During

the first half of the 19th century a second wave of industrialisation

swept through the upper Calder valley. This dramatically transformed the

landscape and the whole social fabric of the district. With the introduction

of steam power, the textile industry moved to the more accessible

valley bottom settlements. These were Todmorden,

Hebden Bridge, Mytholmroyd,

Sowerby Bridge, Halifax,

Elland and Brighouse.

This left more ancient communities stranded on the hillsides and taking

with it an expanding population of millworkers. In Halifax, steam

powered textile factories spread rapidly and by 1850 there

were 24 mills in the town. The largest of which were at Boothtown

(James Akroyd & Son) and Dean Clough (John Crossley & Sons).

Rapid

industrialisation was accompanied by dramatic demographic expansion. By the middle of the century the population of Halifax had risen

to over 25,000. Much of the urban growth in this period comprised

a process of 'infilling'. It involved the

built-up in the central area being more intense. The result was the creation of a series of congested

commercial, industrial and residential courtyards or 'folds'. This

development was accompanied and followed by progressive expansion

from the central urban nucleus, initially to the West and North. It created a Halifax 'conurbation' that led to the municipal annexation

of adjacent territory in Northowram and Southowram townships.

Rapid

industrialisation was accompanied by dramatic demographic expansion. By the middle of the century the population of Halifax had risen

to over 25,000. Much of the urban growth in this period comprised

a process of 'infilling'. It involved the

built-up in the central area being more intense. The result was the creation of a series of congested

commercial, industrial and residential courtyards or 'folds'. This

development was accompanied and followed by progressive expansion

from the central urban nucleus, initially to the West and North. It created a Halifax 'conurbation' that led to the municipal annexation

of adjacent territory in Northowram and Southowram townships.

The

appalling living and working conditions in these expanding mill

towns initially went unheeded. The new textile factories stood

side by side with barrack-like back-to-back slums along the congested

valley floors. While double-decker terraces clung precariously to

the steep hillsides. In Halifax, cellar dwellings and open sewers

presented an ever-increasing challenge to the newly created borough

authority. The booming Pennine town paid little attention initially

to basic public amenities. In 1843 it was described as a 'mass of

little, miserable, ill-looking streets, jumbled together in chaotic

confusion'.

The

appalling living and working conditions in these expanding mill

towns initially went unheeded. The new textile factories stood

side by side with barrack-like back-to-back slums along the congested

valley floors. While double-decker terraces clung precariously to

the steep hillsides. In Halifax, cellar dwellings and open sewers

presented an ever-increasing challenge to the newly created borough

authority. The booming Pennine town paid little attention initially

to basic public amenities. In 1843 it was described as a 'mass of

little, miserable, ill-looking streets, jumbled together in chaotic

confusion'.